Warehouse 13: An Inventory of Forgotten Futures

Every maker has a Warehouse 13 — a place where projects hibernate and artifacts wait. Mine is an attic filled with forgotten futures, half-finished ideas, and the physical history of a life spent building.

Tinkering with Time, Tech, and Culture #32 - Warehouse Series III

Every maker has a Warehouse 13.

That space where projects hibernate, tools multiply, cables self-replicate, and good intentions go to oxidize quietly in labeled (or unlabeled) boxes.

It might be a garage.

A basement.

A storage unit you swear you’ll organize next year.

Mine is literally an attic — the one above my old shop on a couple acres outside Petaluma.

I started calling it Warehouse 13 because, like the TV show, it’s packed with artifacts that have stories attached. Some of those stories are true. Some are embellished. All are part of a life spent building, breaking, soldering, tuning, hacking, transmitting, inventing, and moving on without cleaning up after myself.

Recently I’ve been thinking about preservation — how the maker-hacker era risks disappearing through bit rot, dying hard drives, disposable clouds, and fire-and-forget creativity. And then it hit me:

I’m part of the problem.

There’s a literal archive sitting above my head, and I couldn’t tell you half of what’s in it.

So before I climb those stairs and trigger a nostalgia avalanche, here’s what I remember being in Warehouse 13 — an incomplete inventory of forgotten futures.

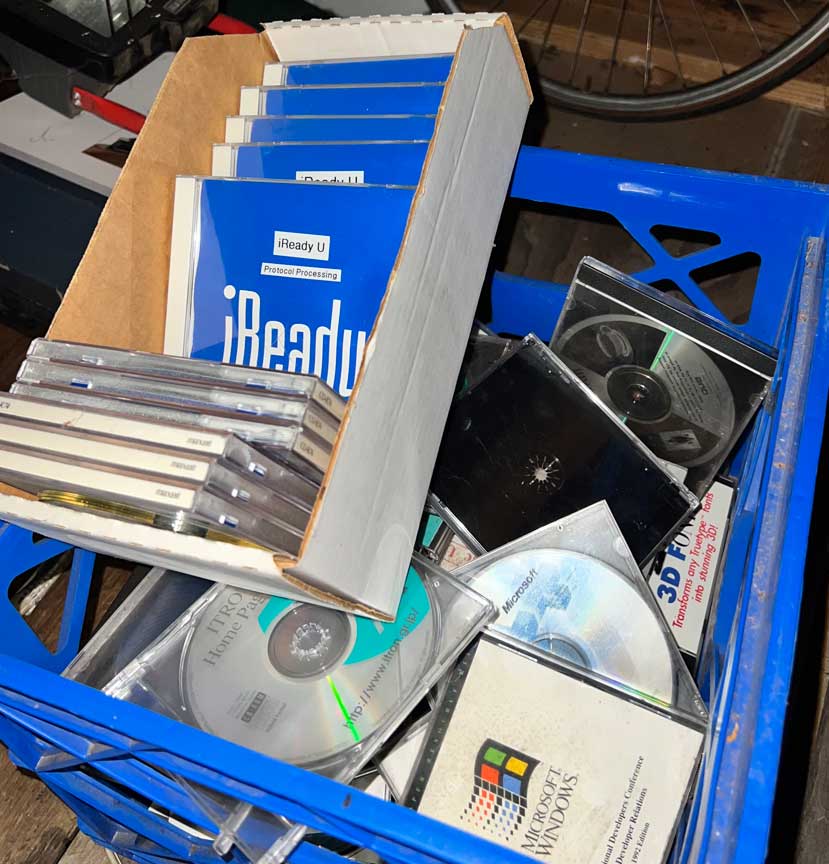

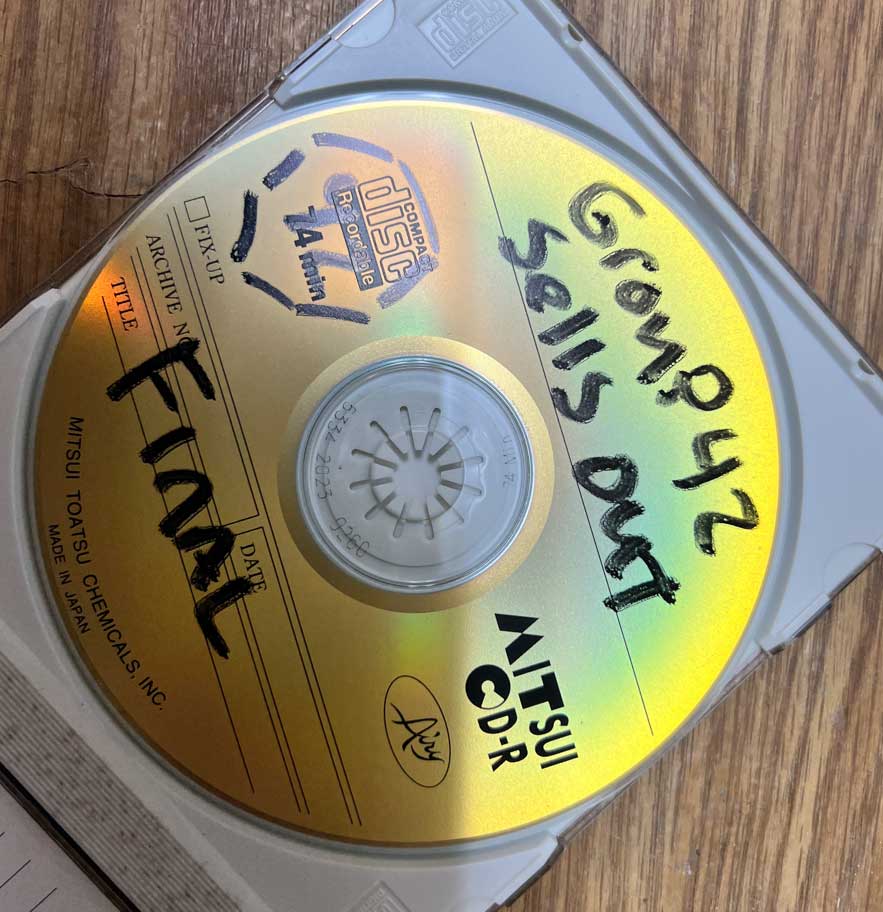

The CD-ROM Archive: Group42 Lives Again (Somewhere)

Let’s start with the obvious:

I have approximately 200 copies of Group42 Sells Out, second production run, 1996.

Professionally pressed discs in jewel cases with printed inserts.

The hyperlinked HTML hacker archive that somehow sold 12,000 copies across three runs — right before the web ate CD-ROMs alive.

Up there is also the January 1996 CD-RW master, the A2 version we used for pressing those 5,000 discs. CD-RWs from that era are notoriously unstable. This one might already be unreadable.

I should check.

I won’t. Or Maybe. Look what I found:

That’s the Warehouse 13 contract: Schrödinger’s Disc stays in superposition until observed.

The HP LaserJet IIP: When Printers Had Dignity

Buried in the stacks is an HP LaserJet IIP from 1989.

Four pages per minute.

300 dpi.

Weighed about as much as an excited toddler.

Peak HP engineering — before the company decided printers should break after 18 months so you’d buy a new one every Earth rotation.

It probably still works perfectly.

Which is why it’s in the attic and not the trash.

Throwing it away would feel like admitting we traded engineering for subscription misery and DRM toner chips.

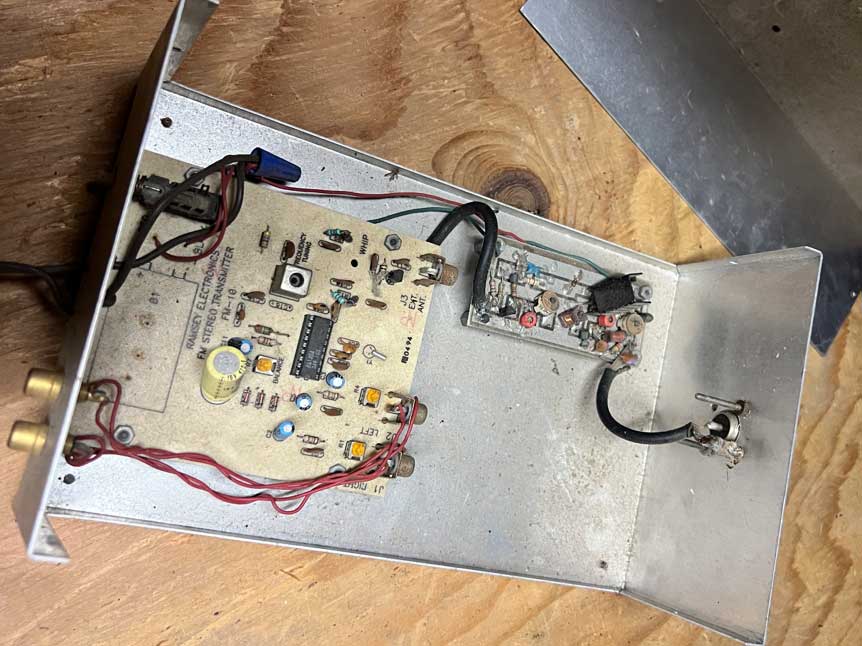

Pirate Radio Transmitters: Illegal, Educational, Glorious

There are multiple production and homemade FM transmitters from my KSUC / Voices through your Head days — various power levels, questionable harmonics, built from parts ordered from catalogs that would ship to a college dorm with zero questions asked.

They aren’t just circuits.

They’re artifacts of the micropower radio movement.

Stephen Dunifer.

Free Radio Berkeley.

DIY broadcasting because “information wants to be free” wasn’t a slogan yet — it was an action.

These belong in a museum.

They're in a cardboard box next to a broken RC car and three half-finished microcontroller projects.

The 8mm Projectors: Machines of Pure Comprehension

At least one — maybe two — vintage 8mm film projectors.

I didn’t buy them as curiosities.

I bought them with a purpose.

I had old films from my grandparents — fragments of family history captured on brittle, shrinking strips of acetate. I tried to save them. Tried to digitize them. Tried to pull images back out of time.

Most of them were already ruined.

Warped.

Faded.

Chemically unstable.

Memories that had outlived their medium.

But the machines themselves survived.

And they represent something important.

A time when technology was comprehensible.

You could see how it worked.

You could take it apart.

You could fix it.

Gears.

Lenses.

A bulb.

No firmware.

No forced updates.

No cloud account required to turn the light on.

The projectors didn’t fail because they were opaque or fragile.

They failed because time eventually wins.

Touching them now is like shaking hands with the ancestors of everything we build today — reminders that preservation isn’t just about saving data, but about understanding the machines that carry it.

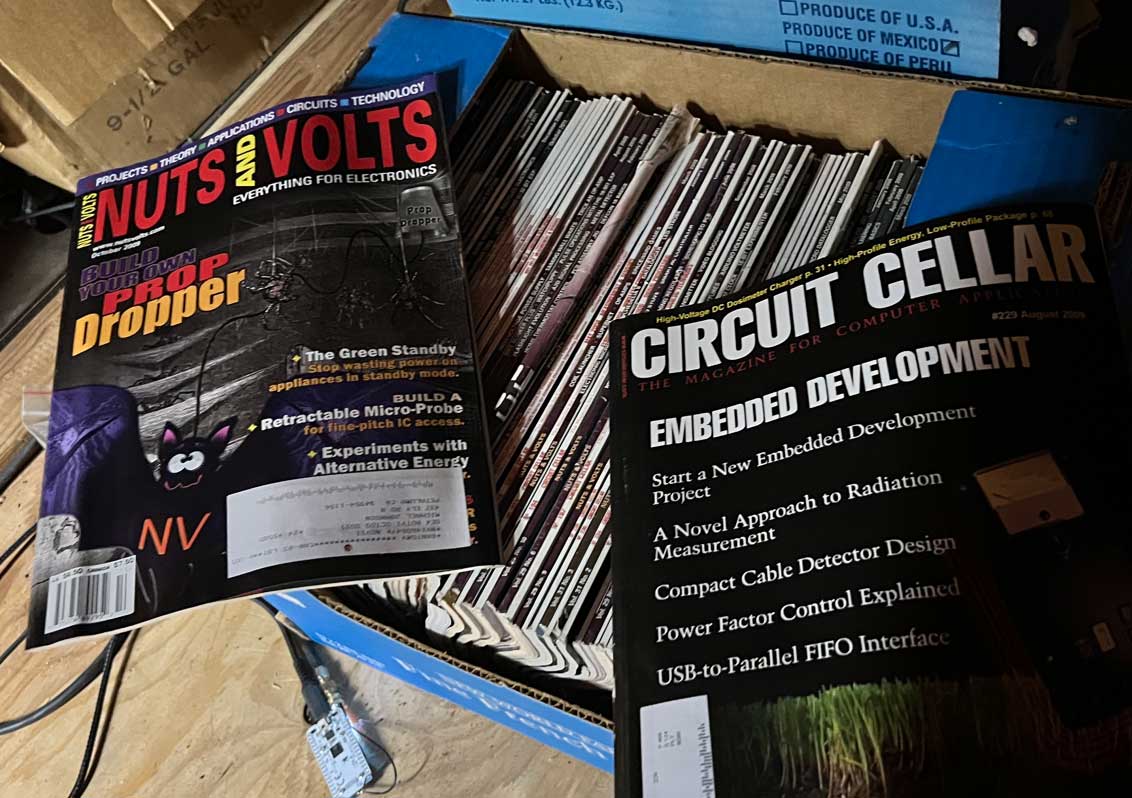

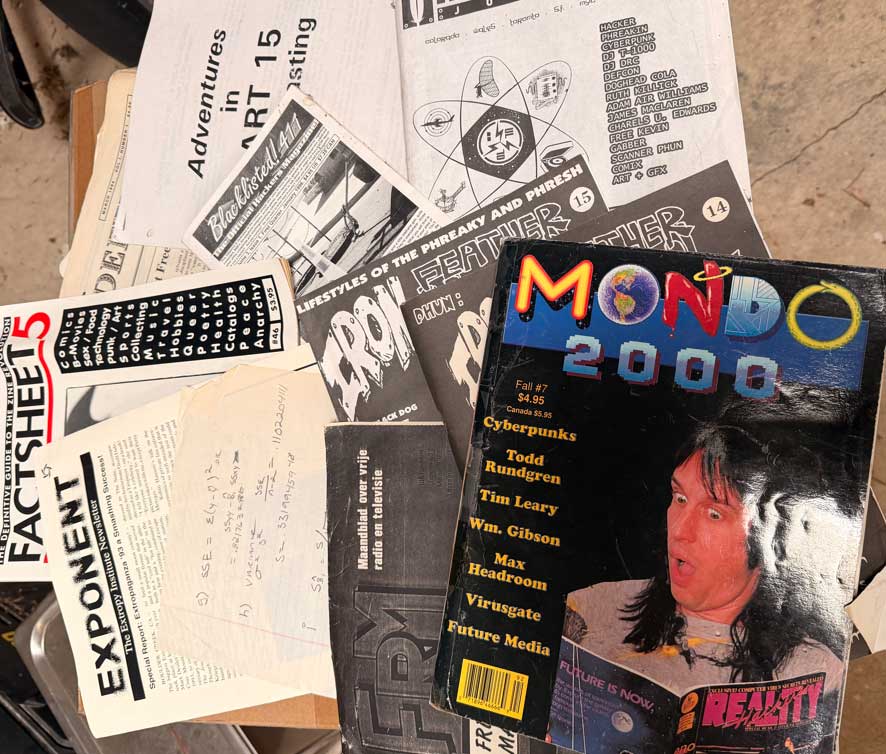

Boxes of Books and Magazines: Hacker Culture in Paper Form

Somewhere up there:

- Stacks of 2600 from the 80s and 90s

- Phrack issues

- Mondo 2000 (all of them)

- Nuts and Volts

- Iron Feather Journal (I wrote for them)

- Technical manuals for extinct systems

- TAP zines

- Maybe some Radio Doomsday materials

This is primary source material for a culture that existed before cybersecurity became a profession, before hacking became corporate, before infosec was a career path.

These zines documented a scene that lived between:

- phone phreaking

- radio piracy

- early computer intrusion

- psychedelic exploration

- anarchist tinkering

- performance art and chaos

Many were printed in batches of 100–200 copies.

Some may be the only surviving issues.

History turns fragile when it exists only in paper.

The Shulgin Book: A Chemical Artifact from Another Era

Somewhere in those boxes is a signed book from Alexander Shulgin.

I met him at a Berkeley party in the early 90s.

Accidentally impressed him by debunking the mescaline microdot myth.

He gave me a signed copy of… something. Not PIHKAL or TIHKAL — something else.

I can’t remember which book.

I can’t remember the inscription.

I just know it’s up there, quietly marinating in dust and cosmic irony.

Half-Baked Projects: Archaeology of an Inventive Brain

This is the bulk of Warehouse 13:

- Circuit boards I never populated, or half populated

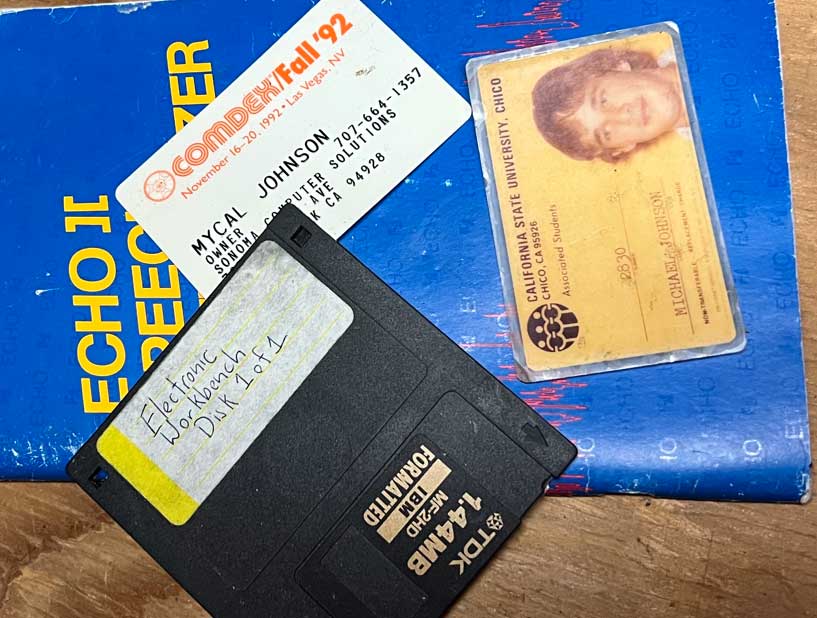

- Codebases on floppies abandoned at 3am

- Radio builds paused mid-solder

- Old CB and HAM radios, antenna tuners, baluns, SWR meters, dummy loads

- Prototypes that seemed brilliant for a single afternoon

- Experiments or parts for experiments I planned but never ran

- Lots of high voltage experiments and parts

- Model Rockets, launchers, Engine casings

- beakers, burners, vacuum pumps, old compounds even a fractional still

- 110 and 2.4 GHz horns and waveguides, magnetrons, and some of the remnants of Herf Guns

- early 900Mhz point to point links, and pre-wifi 2.4Ghz FH networking equipment, even some yagi antennas.

Every maker has these.

These are the ghost footprints of curiosity.

The funny thing?

The unfinished projects are often more interesting than the finished ones.

They show the real process — the thinking, the dead ends, the early sparks.

Nobody preserves half-finished work.

Except attics.

Old Computer Equipment: Touching the Actual Infrastructure of History

An incomplete list:

- ISA cards

- Parallel port dongles

- SCSI cables and terminators

- 5.25" and 3.5" floppy drives

- Megabyte-scale RAM modules

- MHz-scale CPUs

- Token Ring gear

- Coaxial Ethernet cards

- Wallwarts of every size, voltage and amprage

- Enough modems to start an ISP in 1994

Modern computing feels abstract.

But this was the real plumbing.

The infrastructure you could hold, break, and understand.

Sometimes preservation is as simple as remembering how flimsy a 5.25" floppy really was.

Childhood Artifacts: The Human Context

Mixed in with the electronics and hacker relics are:

- Toys

- School projects

- Letters (even love letters)

- Early artwork

- Fragments of who I was before I built things for a living

Not historically important to anyone else.

But essential context for understanding how a 1970s–80s childhood produced a 1990s maker-hacker mindset.

Culture doesn’t begin in adulthood.

It leaks out of childhood.

The Preservation Problem

And here’s the uncomfortable truth:

I’m writing about how hacker history is disappearing…

while sitting under an attic full of primary sources I’m not preserving properly.

- CD-RWs degrade

- Paper yellows

- Electronics corrode

- Boxes collapse

- Bits evaporate

I’m the archivist.

I’m also the threat.

Every maker has a Warehouse 13.

Every hacker has boxes they’ve been meaning to document.

Every piece of history from the early digital era is one garage cleanout away from oblivion.

The Project: Inventory the Attic Before Time Wins

So here’s what I’m going to do:

- Photograph everything

- Document every artifact

- Tell the stories

- Digitize the fragile pieces

- Decide what should be preserved

- Decide what should be donated

- Decide what can finally be thrown away

But first I need to find those attic stairs.

And I need to accept that once I start digging, I’ll uncover things I completely forgot:

- More signed books

- More prototypes

- More relics of a life spent building weird things in weird times

Because that’s what Warehouse 13s do —

they grow when observed.

The Question

What’s in your Warehouse 13?

What are the artifacts sitting in your attic, garage, storage unit, or closet?

What unfinished projects still hum faintly with potential?

What early hardware are you keeping “just in case”?

What fragile pieces of hacker history are stored in a box with no label?

This history is fragile.

It survives only if we do.

Time to climb the stairs.